Dominic Browne talks to FM Conway's David Smith about the intelligence and research behind the scenes that is keeping the firm at the vanguard of the sector.

FM Conway appointed David Smith as director of development in 2013 in order to strengthen its asphalt manufacturing capability, product range and client base. Five years later and having launched the new Gravesend bitumen terminal in Kent, the company says business is booming.

David Smith is something of a smooth operator. With a demeanour that is part Roger Moore and part your favourite teacher from school, he arrived at FM Conway with decades of experience in the highways sector and was charged with boosting sales and manufacturing capabilities. Sources at the infrastructure firm tell Highways this is mission accomplished although it is unlikely to rest on its laurels.

One of the areas where FM Conway likes to set itself apart is in pushing the boundaries of road materials, with the use of recycled asphalt pavement (RAP) a particular flagship offer. The firm has conducted trials with Transport for London (TfL) that set a ‘new benchmark' of 50% recycled aggregate constituents.

Mr Smith says: ‘We are trying to optimise the use of recycled material depending on the use of the road pavement. There are systems within the asphalt industry at the moment that use 100% recycled material. The Americans have a couple of machines now that use hot mix asphalt with 100% recycled material. It's not our ambition because we have quite high traffic densities in the UK and on certain parts of the strategic road network I think that might be a step too far, because you can't control all the parameters in an engineered way to predict the behaviour of the pavement if you start putting 100% recycled in there.

‘The current boundaries in people's minds are 10% of recycled material within the surface course and 50% within the lower layers and those are taken as gospel by a number of people who don't take advantage of the notes for guidance or variation order processes that can be used on the strategic road network. Those processes allow one to talk to the engineer and determine if you can put more recycled material in.

The use of polymer modified bitumen being one of them, he states, following the launch last year of FM Conway's new bitumen terminal in Gravesend, Kent, which produces the company's own.

One issue with recycling aspects of the roads surface is the cost-effectiveness of the process. Mr Smith points out that when you screen material such as recycled planings, the yield of a particular size aggregate, typically 10mm, is very low – ‘usually around 17-18% certainly less than 20%'.

This means if you were to plane off high polished stone value (PSV) materials to get their valuable properties ‘you are actually generating 80% of the material that you can't use under clause 942 [of the Specification for Highway Works]'.

‘What we did in conjunction with TfL, which is very open to sensible debates, is to produce an asphalted concrete, which used up a significant proportion of recycled materials across a range of sizes.

‘We laid it 70mm thick in a single layer to show that we could produce a thickness of construction while at the same time providing a skid-resistant surface in a single operation. That went down several months ago and looked good. It was amenable to being laid around ironwork. We have offered that to the city of Westminster because it was looking to return to something like hot rolled asphalt.'

In trying to establish a more open debate about the boundaries of bitumen and asphalt, Mr Smith questions the very framework around how it is defined. His comments somewhat echo those made by Shell (see pages 18-19) on how the Americans may be more advanced in this area by working towards more performance-based specifications. It should be noted, FM Conway and Shell have a very strong working partnership. Shell provides FM Conway with vast amounts of bitumen every year.

Mr Smith says: ‘In the UK and in Europe the way bitumen is specified is based on two physical properties – penetration and softening point. These are just ways of defining bitumen within some physical parameters. They are not fundamental units. They come from standard tests that are used across the UK, US and Europe, but they don't tell you anything about things like ductility for example, which is very important to the long-term durability.

‘There is a move afoot these days to move away from specifying solely by penetration and softening point towards issues such as ductility and resistance to fatigue.

‘FM Conway has been part of some experiments done by New Hampshire and Nottingham universities looking at assessing some of the performance properties of bitumen so that the predicted laboratory derived property can be replicated in the road.'

He goes on to celebrate Shell's work in ‘engineered bitumen' as he calls it. ‘Shell has a refinery in the Netherlands that produces bitumen that Shell would add components back into – some of the aromatics and asphaltenes that have been removed would be added back in a controlled way to give you more performance properties. This is absolutely the way to go.'

Much of this exciting technology and chemical engineering however is an attempt to return to the fundamental principle of establishing more predictability in the life of asphalt, which is something the market could perhaps respond to with new business models, Mr Smith suggests.

‘One debate we should have to promote innovation and to broaden the ability of contractors to take on a greater variety of materials, is whether there should be some sharing of risk with the supplier. FM Conway would welcome that. And if that had to be given in the form of extended guarantees then that would be something we would be happy to do under the right circumstances.'

Keeping a weather eye on the international scene, Mr Smith is also very aware of outside changes to the fundamental market for bitumen that could end up having as much of an impact on its production as research and innovation from within the sector.

Bitumen varies depending on the crude oil that is refined to actually produce it. There are about 3,000 sources of crude oil in the world and only about 12% are suitable for making bitumen for a variety of reasons, Mr Smith says.

Coupled with this scarcity are two main market forces – both diesel and heavy fuel oil are in decline due to air quality issues. Diesel cars look like they are on the way out and the International Maritime Organisation has issued a set of regulations that says ships will no longer be allowed to burn heavy fuel oil from 2020 because it contains about 3.5% sulphur and so when it is burned it reduces air quality. Retrofitting refineries to not produce those heavier elements is a seriously costly business that can run to hundreds of millions of pounds.

‘The end result is some people may not make bitumen anymore because the demand is in the light distillery functions. That is the biggest bulk area of the future demand. Refinery capacity in Europe has dropped by about two million barrels a day over the last five or six years and that's because a significant number of European refineries are of an age where it is not worth spending a billion dollars to retrofit them.'

With all the potential disruption washing around the sector, one question companies are often asked is whether they know their core value. Mr Smith doesn't appear to be easily ruffled and takes this question, like most other things, in his stride.

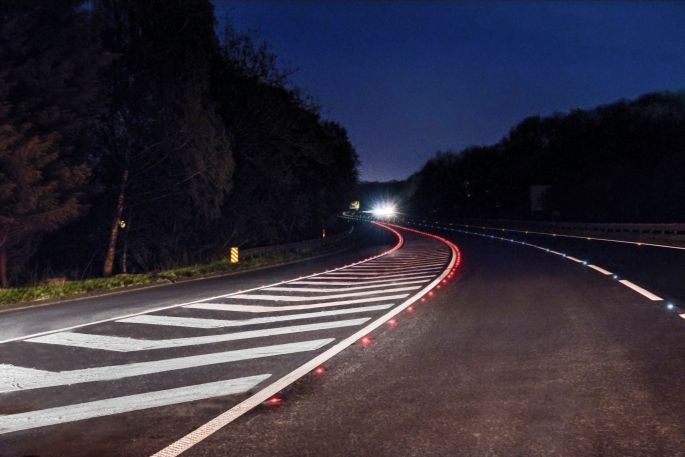

‘Our core value is highways maintenance. There will always be vehicles and asphalt is an ideal material. The reason we use it is because of its ease of use. As far as the electrification of the highways sector is concerned we are pretty safe. We are already putting in digital receptors on behalf of our London boroughs. We have put in vehicle charging points in anticipation of electric vehicles. We have a very sound model especially as we can recycle the existing asset back into our materials.'